Creasy's Column for Reel Life October 2017

- 30/10/2017

By Hugh Creasy

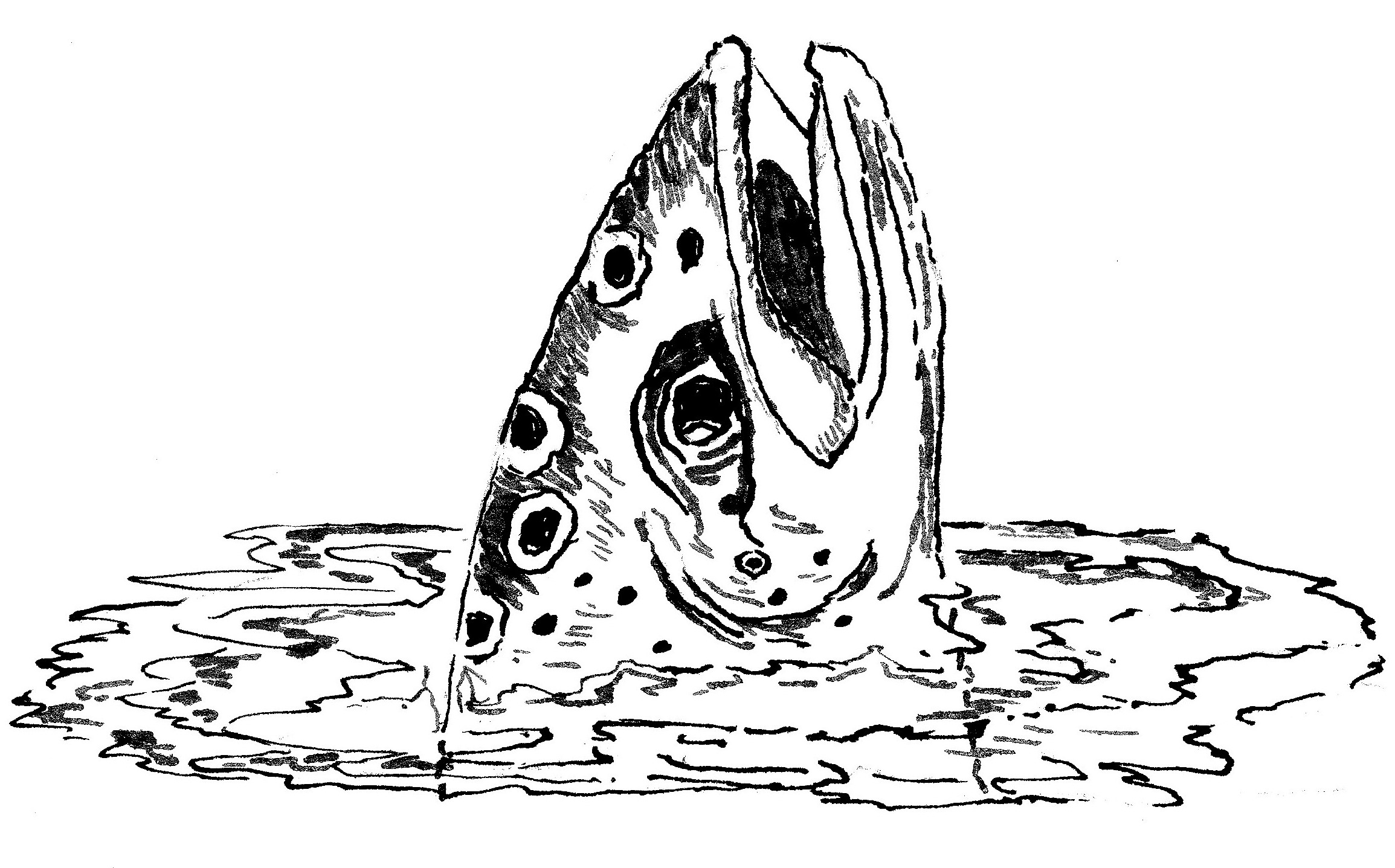

In the hills where bright water flows clear and clean, filtered by tree roots and silvery gravels, young fish, parr-marked and swift, swim the pools and runs. They gather in schools and when it rains and streams run bank to bank, these young fish go with the overpowering flow, downstream through high country valleys where snow-melt clouds the water, down through forest-shaded rapids and tumbling over shallow waterfalls, driven by the power of the spring flood and powerless in its might.

They swim where they can and some find shelter from the flood, behind bedrock deformities in the streambed and in the back currents created by stable boulders and the twists and turns of the valley floor. But the majority, numbering in their hundreds, are driven on towards bigger waters and great danger. Their numbers have already been thinned by predators and competition. The weakest were taken early, many before they left the redds. The survivors still have strength, and as the power of the flood dissipates they wash into the force of the main river.

On a boulder, white-streaked with ordure, a white-faced shag spreads its wings to the sun. On a nearby totara, skeletal and dead-branched, the shag’s partner flies to a straggly nest and regurgitates a pulped mass of fish into the gaping mouth of its chick.

Below the dead tree, where the stream falls into a wide pool at the head of a long reach, the young trout tumble. They circle their new surroundings, holding a tight formation. The pool’s breadth and depth are strange to them and they swim with a wariness they will need if any are to survive to maturity. For an hour or two they are safe from the menace from above. The shags have dined well on another school of young trout that fled the pool and dispersed in a downstream rapid.

There is still a menace from below. An eel, sinuously loops through gaps in the stream bed, pausing, mouth gaping and gills pumping, aware of the young fish, through smell and movement. It tastes blood, invisible but enough to awaken its hunting instinct.

At the tail of the school of young trout, an injured fish struggles to keep pace. In the tumble over boulders its skin was torn and its flank bruised – enough damage to interfere with its swimming action. It gives off a strange vibration. The eel waits as the school passes, then lunges, its mouth snaps shut on the injured fish and after a brief struggle its life is over. Shreds of the dead fish fall to the bottom of the pool. From crevices between boulders and bedrock crayfish emerge to feed, their claws extend daintily to grasp the moving morsels. The nymphal forms of mayflies, stoneflies and caddis extend clawed feet to grasp the tiniest particles, and in the shallows water boatmen take their share. There is no waste.

A dead fish is a treasure to the life of the river. Even those creatures that do not directly feed on its flesh take advantage of the carelessness of those attracted by its presence. In calmer waters dragonfly larvae are lethal hunters of smaller creatures, and dobsonfly larvae hunt the shallows for careless nymphs.

Small trout feed on small insects. If there are enough of them a young trout’s growth will accelerate at a phenomenal rate, and within a few months it will be large enough to fend off all but a few predators, and most of those will be sea-run.

But time has passed for the school, and pangs of hunger stir to life the dozing shags. They spread their wings and croak their calls. With a swift clatter of flight feathers they leave their perches, beady eyes alert for movement. They fly for some distance before diving, perhaps to engorge their flight muscles with blood to sustain them in chilly water. Then they dive and with light splashes they enter another world where, with peculiar swimming motion, they seek their prey.

The trout are alerted by the splash of the shag’s entry and dart about, trying to keep formation, but the birds, with as much skill under water as they show in flight, break the formation and the fish scatter in panic. The slowest are easily taken, while the swiftest and luckiest head for the tail of the pool and the rapids below. There they find temporary refuge in backcurrents in fast water.

Their journey has just begun and already their numbers have been heavily thinned. They left the redd in hundreds and now number only in double figures. They have yet to find safety. The need to feed will keep them on the move until they are large enough to win battles for the best holding water. Some will run to sea and face predators much larger than any faced in the river. Only the swiftest and fittest will survive to return to the river and resume the dominance battles that will see their progeny once again take part in the eternal circle of survival.

When an angler brings a fish to the net, and admires its perfection of form and function, its beauty of colouring and the way it fought to survive, he or she is looking at the very best that natural selection has to offer – the best that the river can produce, and a survivor against the odds that deserves our deepest respect.