Creasy's Column for Reel Life September 2018

- 27/09/2018

By Hugh Creasy

At last the river has cleared, but still it runs high from snowmelt in the ranges. There are logs strewn on the banks – deadwood from clearfells further upstream, and they are hairy with branchlets that will catch a carelessly cast spinner or fly. Through a maze of detritus a thick school of whitebait runs. A shag takes its toll and with thickened crop it perches atop a bare-branched pine and croaks to its mate building a nest in the fork of the tree.

The sun lifts above the horizon, brightening the dance of swallows taking sandflies and gnats in swooping glides, seeming to defy all laws of gravity that hold humans firmly to the planet. Although a footstep in the fast moving current proves that gravity is not powerful enough to make wading safe. The power of the river is all too apparent. Casting will have to be from the shallows and the bank. As the sun rises and warms the air, a flight of damsels hovers above lupin flowers hanging over a shallow pool where bullies dart, alert to footsteps from a careless approach. The pool is too shallow to hold trout, but it holds life, with backswimmers and water-boatmen busy at the edges and bloodworms strewn among the stones where caddis larvae cling to the undersides of boulders.

These are the survivors of winter floods. Only a week ago the river was roaring from bank to bank, thick with mud from slips in the high country. The height of the flood can be seen on the willows along the banks. Old chemical drums sit in branches, high off the water, along with metres of fencing wire and plastic wrap from bales of hay fed out during the winter. There is a smell in the air, of decay. Somewhere a carcass has caught up in the foliage. The flow has not yet passed through towns and villages where plastic and paper will add to its burden.

A family of mallards waddles to the shallows, well upstream, the youngsters huddling close on their first venture out. They number close to a dozen, a necessity of survival when the attrition rate is more than 80% before maturity.

In the air a hawk circles, lazy on an updraft of reflected heat. There will soon be road kill to feed on when the family of rabbits safe in its burrow releases its youngsters. They have stayed well above flood level, in a burrow dug into gravel left from roadworks, and they feed in the evenings on fresh young dandelions and shoots of cocksfoot. The little ones bounce with energy and fearlessly seek adventure. Adults teach caution with a thump of a hind foot that sends the youngsters scurrying for cover.

Into this world of hunters and hunted the angler comes, tentative on a first venture out during spring. He slips and slides on riverside rocks, clumsy this early in the season, and he bends to the river bed, tipping over stones in the shallows, checking for life that will determine what fly he will use. He would really be better off using a spinner or live bait if he wants to catch fish, and he sees the truth of this when Dobson fly larvae, large and ready to moult, scurry for cover in the muddy shallows created with each boulder rolled over.

But the angler is a fly fisherman. He has endured a winter of discontent as front after front drenched the land and kept him indoors.

From his flybox he selects a well-weighted caddis imitation, cream bodied with a simple tuft at the head – a free swimmer copy that might tempt a strike.

There are backcurrents behind boulders and pockets of calm in the riffles. A line of bubbles indicates the main flow, where fish are more likely to be. Experience has taught the angler to fish his feet first, and he casts to pocket water, progressing from the tail of a run to its head and beyond – short casts at first progressing to longer and longer cast as he covers all the water.

Some of his casts are rough and splashy - early season casts that will progress with more finesse as time and practice make perfect. The small indicator above the fly jerks to a stop and the angler flips the rod tip to set the hook. It sets on nothing. Too much loose line between the rod tip and the fly. The indicator floats free and the fish is lost. To cast to the main flow, his line must cross some smaller flows, and it is these that will cause drag and an unnatural movement to the fly. To overcome the effect of drag, the angler has to cast a loose line, allowing his nymph to sink and travel in a natural manner for as long as possible. If his indicator stops he has to strike with a high lift of the rod in his casting arm, and a downward pull on the line in his other arm, to take up the remaining slack line. It takes practice and concentration to get it right, attributes absent in this angler, and his frustration boils over.

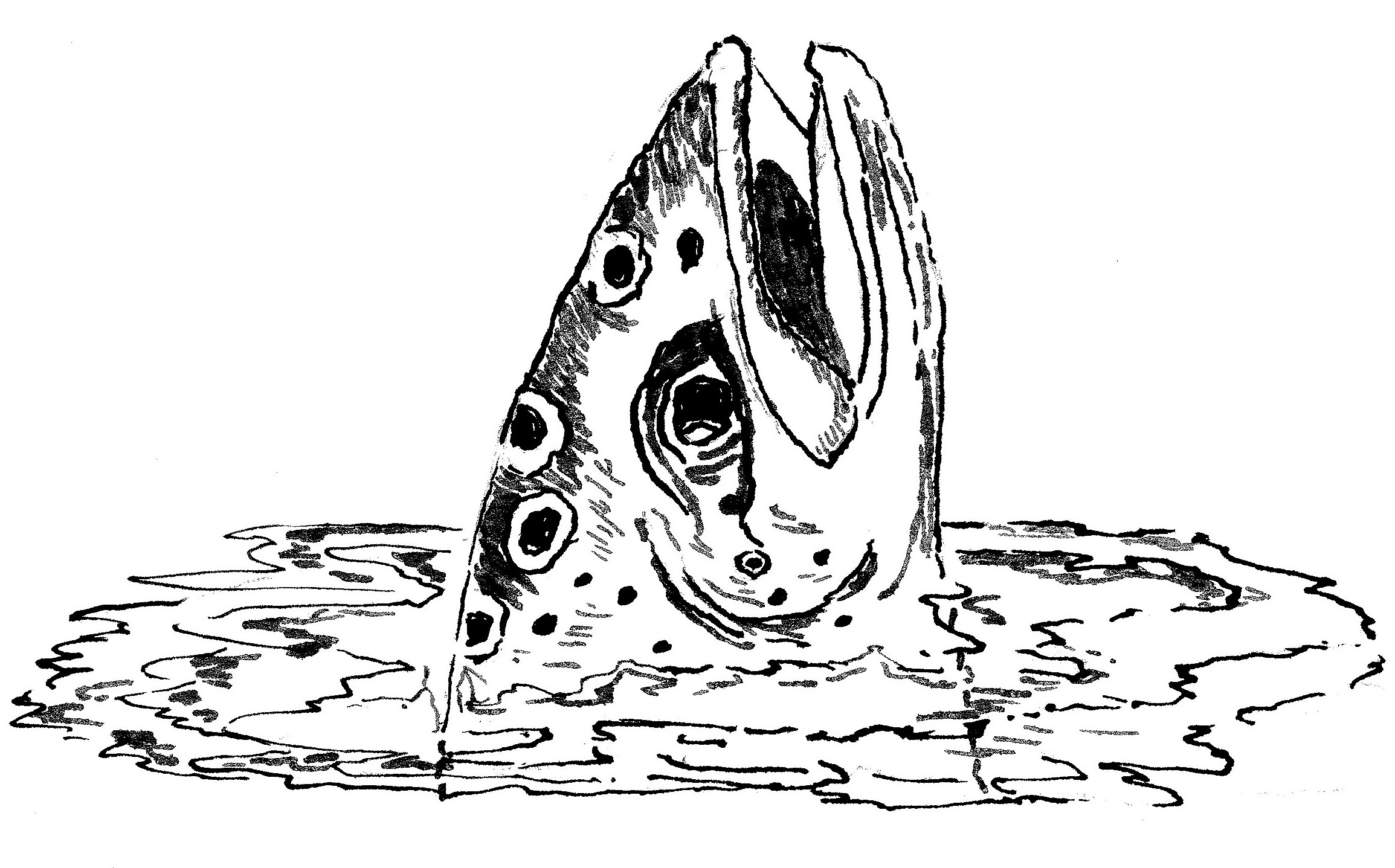

He retires to the bank and rests a tired shoulder. On a quiet stretch of water mayflies rise, just a few as the sun’s heat grows, and an upstream breeze helps them lift off the water. A fish’s tail breaks the surface and a boil of water marks the lie.

A kingfisher calls its single note and it flashes jewel-like in a dive to a streamside nest. The angler is unaware of its beauty, his concentration locked on that small boil. Hope springs once more and he has one more decision to make. What fly to imitate that insect’s rise?